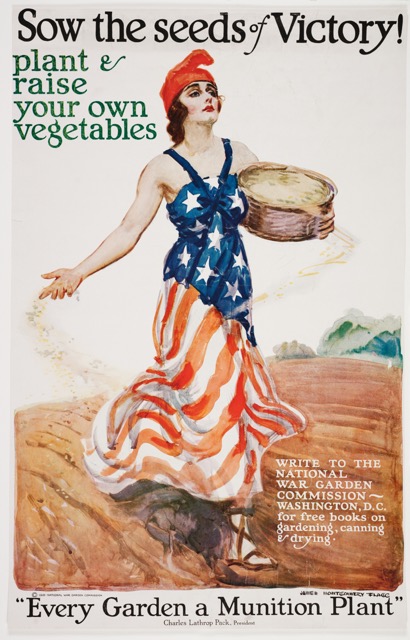

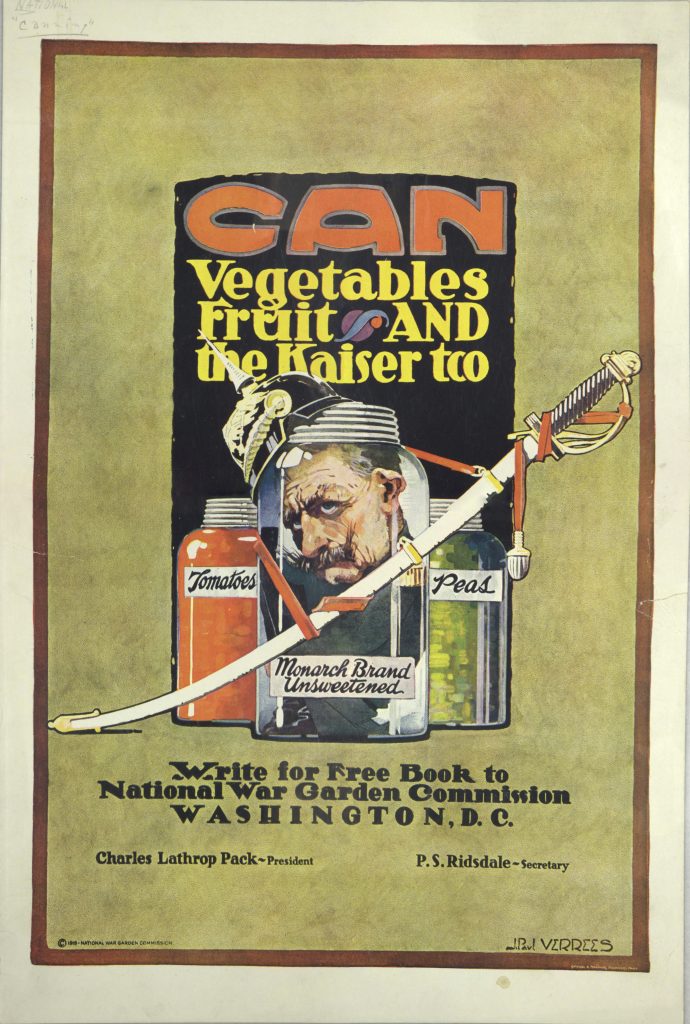

Can Vegetables, Fruit and the Kaiser Too. [Washington, D.C.] : National War Garden Commission, 1918. http://archive.org/details/CAT31123280.

First, a warning: you should never make a historical pickle recipe (yes even if it is your great grandma’s). We know a lot more about food safety now and it is very important to use tested recipes when fermenting, and especially when canning. Now, you might be wondering how I plan to follow my own safety advice when the conceit of this blog is making historical recipes. The answer is, I’m making a modern recipe, straight from the well tested pages of the University of Wisconsin’s food preservation series. I think Tingle would approve of using new science to improve food preparation, but more importantly I don’t really feel like risking botulism over a blog post.

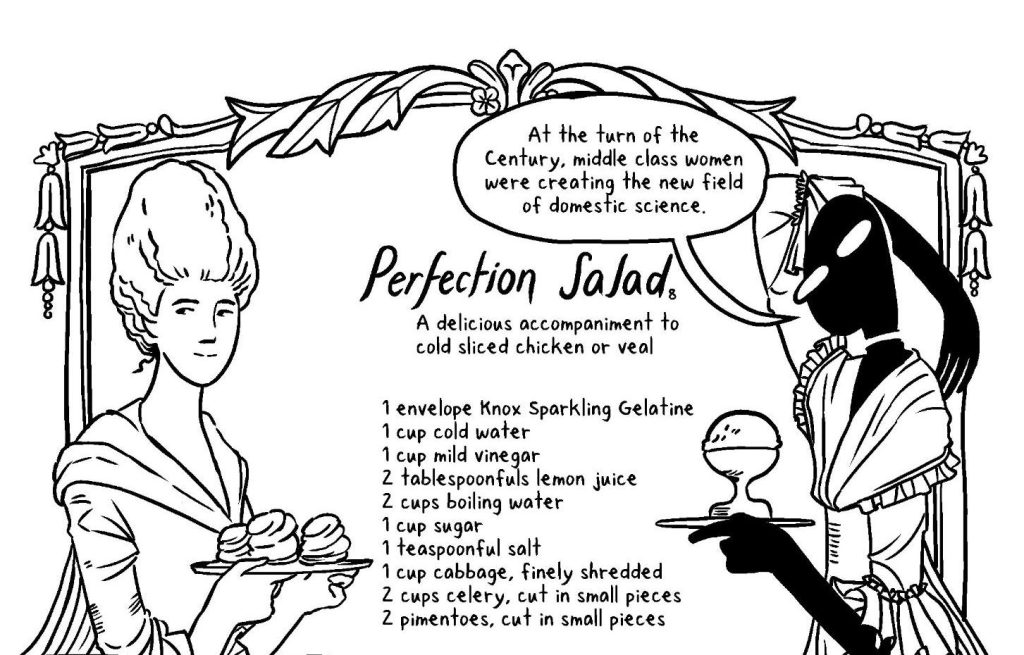

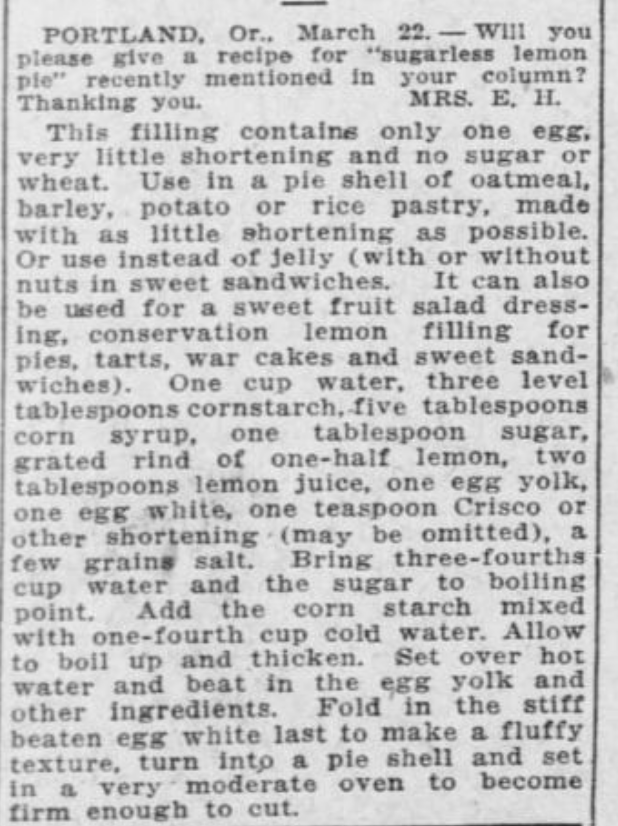

So why am I writing about pickles if I’m not even going to use a proper Tingle recipe? Well, even though I’m not using one of her recipes, pickling and canning were a large part of the column. Pickling is an ancient method of food preservation, dating back to at least 2030 B.C., but industrial canning was new in the early 19th Century and home canning was just emerging.2Avey, Tori. “History in a Jar: Story of Pickles | The History Kitchen.” PBS Food (blog), September 3, 2014. https://www.pbs.org/food/the-history-kitchen/history-pickles/. It was scientific, and particular, not something young women could learn from their mothers and grandmothers who didn’t grow up with home canning. It was also hugely popular, an inexpensive way to preserve food when it was plentiful and inexpensive. It was just the kind of thing that people had a million questions and worries over.

Tingle and her Audience

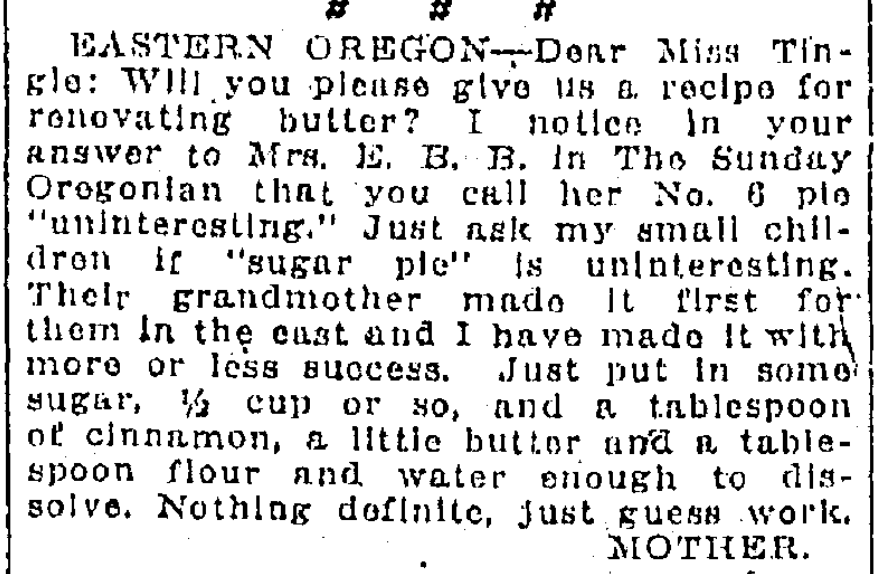

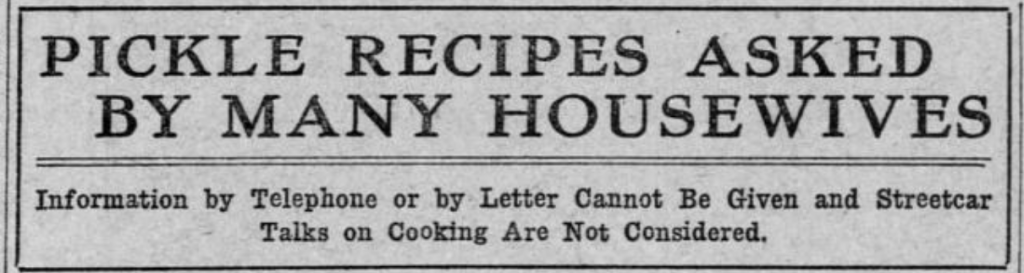

Pickles also highlight the ongoing tension between Tingle and her correspondents. It raises questions about how Tingle’s correspondents viewed their relationship to Tingle, how they influenced the column, and how Tingle responded. In addition to her correspondents column, Tingle often published articles on specific topics or dishes. These articles weren’t wholly separate from the columns, she often referenced correspondents’ questions, or wrote long form articles upon receiving an overwhelming number of requests. In September, 1912 Tingle wrote an article about Pickles:

“This article is about pickles and relishes. I thought it was to be about “Cooking for Diabetics,” for I have had such a lesson promised for a long time. But this week brings requests for so many pickle receipts that no ordinary correspondence column will hold them, and so a sort of “overflow meeting” will have to be organized. I was planning a nicely classified series of “lessons” on pickles and such seasonable matters; but, today, I feel that it is wiser to give some few recipes ‘as they come,’ regardless of classification or general principles, since people tend to ‘want what they want when they want it.” and I don’t want to be besieged (as I have been lately) by phone, by letter, and in streetcars by passionate demands for dill pickle directions, or requests for relishes. Let me say again, however, that it is not possible for me to give information by telephone, or by letter, and that streetcars were not really intended by Providence as theaters for cookery lectures.”3Lilian Tingle, “Nine Ways of Making Pickles,” Sunday Tingle, Lilian. “Pickle Recipes Asked by Many Housewives” Sunday Oregonian, September 1, 1912, sec. Five. Historic Oregon Newspapers. https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83045782/1912-09-01/ed-1/seq-58/#words=LILIAN+TINGLE.

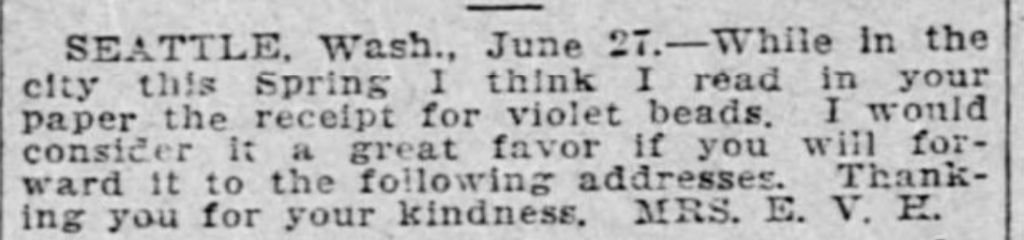

This is one of many examples of Tingle’s correspondents shaping the column, insisting it meet their needs rather than conforming to Tingle’s domestic science agenda. It also illustrates the strength of the bond between Tingle and her correspondents, and the sense of urgency and even entitlement some of her correspondents had. Especially in the early years, Tingle was constantly reminding correspondents that she couldn’t answer questions by phone or send personal letters. Her frustration mounted over the years as correspondents continued to expect personal replies, and even, according to this article, accost her on the streetcar. Just a few years before her 1912 pickle article she wrote an article decrying pickles, claiming they were dangerous for children and young women: “the craving for pickles is almost always a danger signal with growing girls.” Still, she continued to publish pickle recipes year after year. In fact they were one of the most popular requests. In the end, Tingle caved to the pressure of her correspondents, giving them what they wanted instead of what she thought was best. She concluded, “I must remember that I am not writing a sermon on dietary sins, but simply trying to answer requests for pickle recipes which have been pouring in lately.”4Lilian Tingle, “This Is Open Season for the Deadly Pickle,” Sunday Oregonian, August 21, 1910, sec. Six, Historic Oregon Newspapers, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83045782/1910-08-21/ed-1/seq-63/#words=pickle+PICKLE+Pickle+pickled+pickles+pickling+TINGLE.

A parasocial relationship (PSR) is traditionally defined as a one sided relationship between audiences and celebrities. Audience members form emotional connections to people or characters that do not know they exist. Online creators have increasingly and explicitly discussed parasocial relationships publicly. The internet has undeniably intensified these relationships by giving audiences more intimate access to creators. While audiences also form parasocial relationships with traditional celebrities, the internet intensifies them. Tingle and her audience are an interesting juxtaposition. In many ways Tingle’s correspondents did have a parasocial relationship with her. She was more available than any traditional celebrity, and entered the private kitchens of thousands of women. But that relationship was mediated by letters and a newspaper, not social media.

In “The one-and-a-half sided parasocial relationship: The curious case of live streaming” internet and communication researchers Rachel Kowert and Emory Daniel Jr. argue that live streamers (on Twitch or YouTube, for example) represent a slightly new twist on the traditional PSR. Rather than a one-sided relationship, live streamers and their audiences have a one-and-a-half-sided relationship because of the increased opportunity for reciprocal communication. Unlike traditional celebrities, live streamers interact constantly with their audience, responding to chat messages and talking live on air, making the audience feel even more connected to them. The authors argue that the increased accessibility of streamers creates the, “potential for reciprocal communication, a stronger sense of community affiliation, wishful identification, greater emotional investment, fandom cultures, and an increased sense presence than traditionally experienced in parasocial relationships.”5Kowert, Rachel, and Emory Daniel. “The One-and-a-Half Sided Parasocial Relationship: The Curious Case of Live Streaming.” Computers in Human Behavior Reports 4 (August 1, 2021): 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100150. While Tingle’s column is very different from live streaming, it shares the increased potential for reciprocal communication, strong community affiliation and wishful identification. Tingle responded to thousands of letters, was a role model viewed by many as the peak of female domesticity, and through the column helped facilitate a community of cooks. Her correspondents expressed many of the positive emotions and outcomes expressed by people in parasocial relationships. They felt supported, like they had someone to help them, and a community to lean on, just like many people in live streamers’ audiences. Tingle often referenced personal parts of letters, thanking her or telling her personal stories that she didn’t print. Correspondents felt close to her, close enough to tell her their stories, ask after her health and about her travels, miss her when she took a break, and let her into their personal struggles in the home.

Tingle also dealt with some of the drawbacks online creators face today, including fans who constantly tried to access her and sometimes crossed her boundaries. She also experienced some of the joys. In 1922 she wrote, “I find I have a number of ‘unknown friends’ of many years standing. I have learned to recognize certain handwritings and initials with pleasure as old friends even though I know neither the names nor faces of the writers. One such friend wrote recently that she had been reading my column regularly for 12 years! I felt very much pleased and very grandmotherly.”6Lilian Tingle, “Answers to Correspondents,” Sunday Oregonian, March 12, 1922, sec. Five, Historic Oregon Newspapers, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83045782/1922-03-12/ed-1/seq-72/. Maybe even more than live streaming, Tingle had a truly one-and-a-half sided relationship with her correspondents. She personally read and responded to their letters over years and decades. However, the pace and degree of emotional connection was undoubtedly very different. The internet facilitates much faster, and more intense communication especially through the medium of live video. The column was an analog anonymous forum, run by a proto-micro-celebrity. Many of the trends we see today in online cooking spaces were present in Tingle’s column and have only been intensified by the internet.

But Back to Pickles

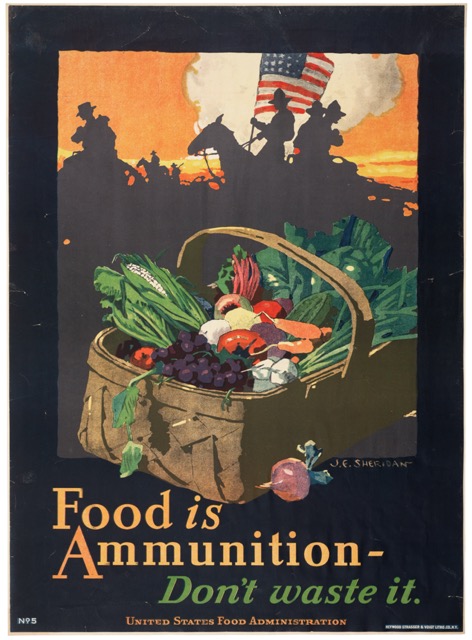

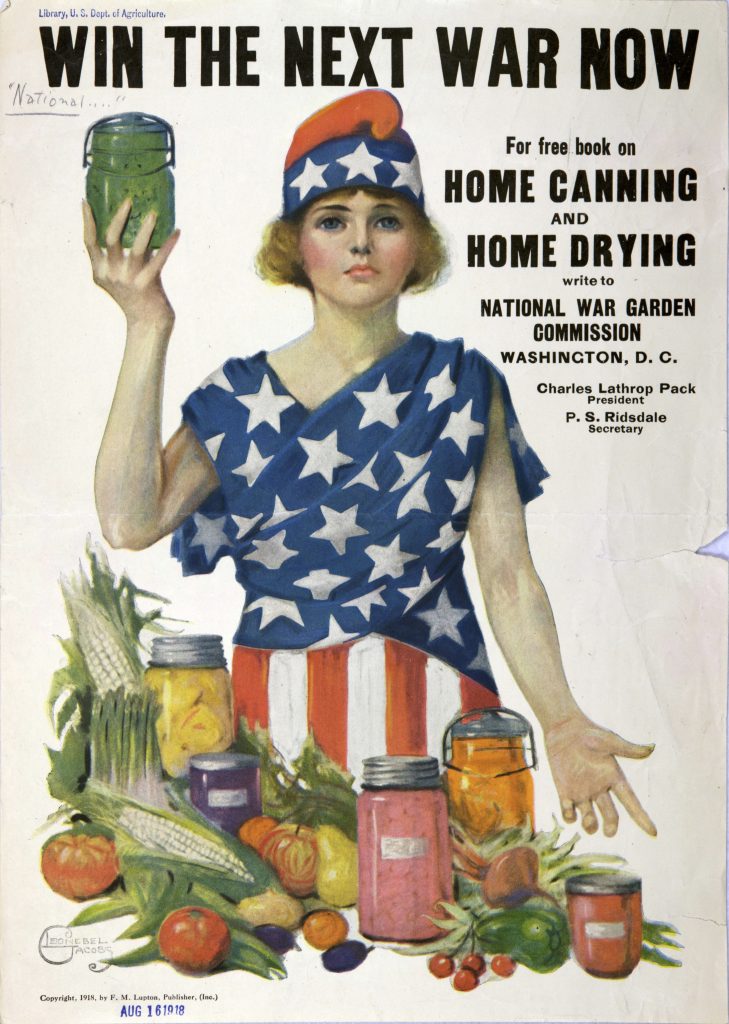

Home canning started to gain popularity in the early 1900s, and the USDA released its first pamphlet with instructions for safe home canning in 1909.7Andress, Elizabeth, and Gerald D. Kuhn. “Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations.” In Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 1998. https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/usda/review/earlyhis.htm#bul359. Every summer and fall, Tingle’s column with questions about canning, from pickles to deviled crab. Jams and preserves were hugely popular, as well as whole vegetables, and meat, canned for the winter while ingredients were cheap and fresh.

Food science didn’t quite keep up. Today we know that certain high acid foods may be canned using a water bath canner, essentially submerging cans in boiling water for set lengths of time. But low acid foods may only be canned safely using a pressure cooker. Without a pressure cooker there is no way to heat an entire jar of food to the proper temperature and botulism and other poisonous bacteria can survive. By 1917 the USDA started to recommend pressure canning for low acid foods, but home pressure cookers were still fairly new, difficult to use, and potentially hazardous. So it took a while for the general public to fully make the switch.Andress, Elizabeth, and Gerald D. Kuhn.9“Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations.” In Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 1998. https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/usda/review/earlyhis.htm#bul359. When Tingle started writing the column in 1908 the USDA hadn’t even released official home canning recommendations, women turned to her for the most up-to-date scientific advice, and to learn about government reports and recommendations. Food science of canning and recommendations for home canners developed over the course of Tingle’s column and her recipes changed to reflect the new science. Home canning is a perfect example of the ideal of domestic science. It requires precision, specialized knowledge, and expertise. Young women had to turn to experts and “rationalize” their cooking.

Tingle’s correspondents were excited about canning, but many were apprehensive. One genre of letter Tingle regularly received was women describing their canning process in intricate detail and begging Tingle to ease their mind and tell them if their food was safe. This “young bride” from Clackamas, OR wrote a typical letter: “I canned some frozen beef last winter. Now, I wonder if there would be anything poisonous in it. Boiled it in jars for four hours. I always have good luck with meat, but since canning this have wondered about it. It was killed about 10 days before canning (during cold weather).”10Lilian Tingle, “Answers to Correspondents,” Sunday Oregonian, May 7, 1922, sec. Five, Historic Oregon Newspapers, https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83045782/1922-05-07/ed-1/seq-76/. Tingle assured her correspondent that the sterilization period should be sufficient but never to eat anything that looked or smelled off. Today, experts would never recommend eating any canned meat not made in a pressure cooker, but this was 1922, the scientific consensus wasn’t in (or hadn’t quite reached Oregon), and home pressure cookers were less available.

Pickles, on the other hand, don’t need a pressure cooker. The acid in pickles comes from either added vinegar or fermentation. For fermented pickles, the cucumbers are put in a salt brine for several weeks and, “salt-tolerant bacteria convert carbohydrates (sugars) in the vegetables into lactic acid.”11Ingham, Barbara. “Homemade Pickles & Relishes.” Wisconsin Safe Food Preservation Series. University of Wisconsin, 2002. https://foodsafety.wisc.edu/assets/preservation/B2267_Pickles_08.pdf. Then the fermented pickles are canned. The other option is quick pack pickles: the cucumbers are packed in jars with a pickling solution containing vinegar and canned immediately. For either method, exact ratios are very important to ensure the correct PH and safe canning. That’s why it is so important to use a (modern) tested recipe. Sure, lots of people used Tingle’s old pickle recipes, but lots of people also died of botulism poisoning.

Making the Pickles

I decided to make two types of quick pack pickles: dill and bread and butter. Dill pickles would usually be fermented and then canned, but I wanted to do all my canning in one day, so quick pack it was. The most challenging factor was getting the ingredients and equipment. It is not quite pickling cucumber season, really I should have waited until at least July, but I settled for waiting until mid-May. I was able to get some small organic cucumbers from Sundance, which are at least better than the huge cucumbers from the grocery store.

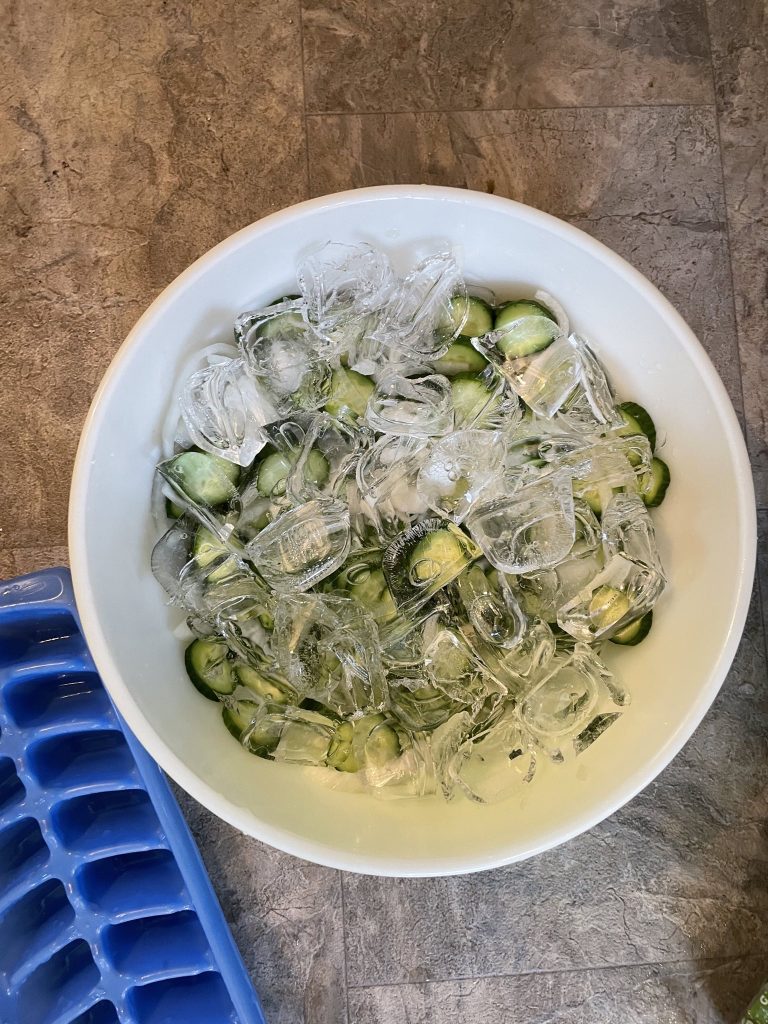

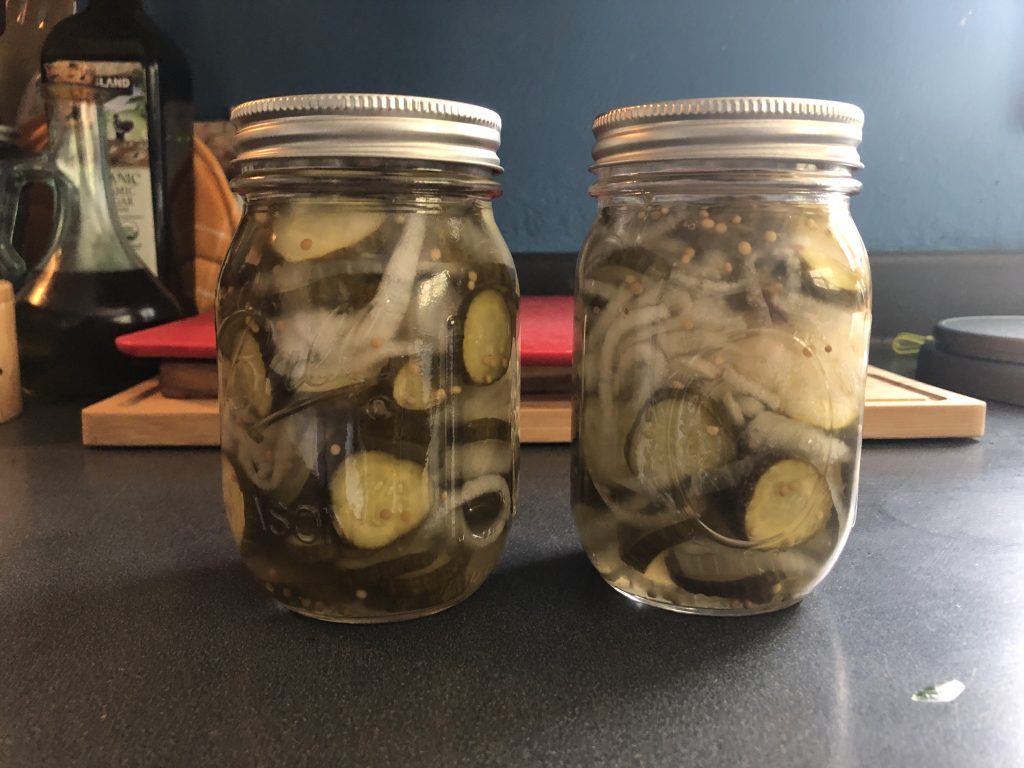

My mom canned her homemade raspberry jam every summer, so I have a little bit of experience, but not a ton. I also don’t own a proper water bath canner, or canning tongs. Instead I used the biggest pot I own and a rack to keep the jars off the bottom so water could circulate. Luckily my friend had some brand new jars and lids so I didn’t have to buy those (you can reuse jars, but it is very important to buy new lids each time you can). Making the pickles was pretty easy. After a lot of research I chose two recipes from the University of Wisconsin’s Safe Food Preservation Series: Pickles and Homemade Relishes.12 Ingham, Barbara. “Homemade Pickles & Relishes.” Wisconsin Safe Food Preservation Series. University of Wisconsin, 2002. https://foodsafety.wisc.edu/assets/preservation/B2267_Pickles_08.pdf. The bread and butter pickles were thinly sliced, kept on ice for three hours, and then canned in a pickling solution of sugar and vinegar (heated to boiling). Getting the jars in and out of the canner was a challenge without canning tongs, but I only splashed boiling water into my face once.

The dill pickles were supposed to be canned whole, but since I was using pint jars, and big cucumbers, I decided to cut them into spears so I could get more than two into each jar. The pickling solution for the dills was similar: vinegar, water, salt and sugar. I added dill, mustard seed, and red pepper flakes to each jar.

My favorite part of the process was watching the cucumbers go from a fresh, vibrant green, to the muted green of pickles as they cooked in the canner. After I removed the jars and they started to cool, the lids popped down which means they sealed properly. I can’t help but feel some of the anxiety Tingle’s correspondents expressed. Even though I followed the recipe as best I could, I still have a few lingering doubts. What if the water wasn’t boiling enough? What if I contaminated the jars? What if spearing the cucumbers breaks the recipe? I can see why canning was such a popular source of questions. I guess my best recourse is more googling, or perhaps leaving a comment on a blog post about pickle making.

Notes

I used recipes from the University of Wisconsin’s Safe Food Preservation Series. Quick pack bread and butter pickles (page 20) and quick pack dill pickles (page 21).

Click on in-text citations for references or go to this page for a full list.

Special thanks to A. McNamee for help with the canning and the jars.