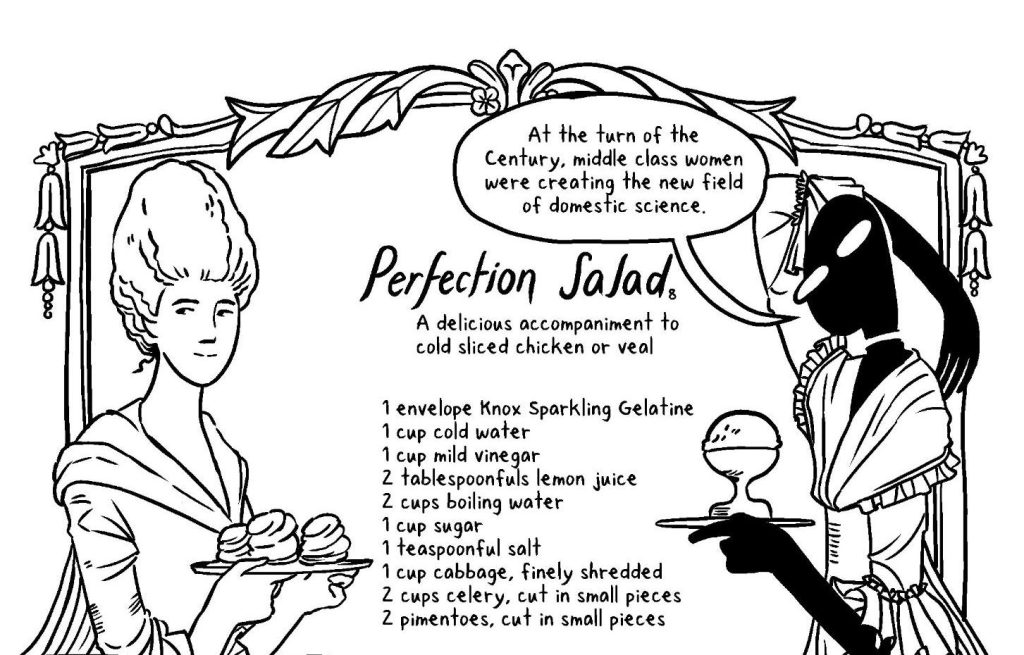

In mainstream U.S. culture today “salad” evokes leafy greens and fresh vegetables, maybe some cheese, a walnut or even the occasional fruit. The general consensus is that gelatin will not be involved. In the early 20th Century, however, jellied salads were a new, exciting way to contain otherwise messy salads, and turn them into a perfectly controlled, feminine delicacy.

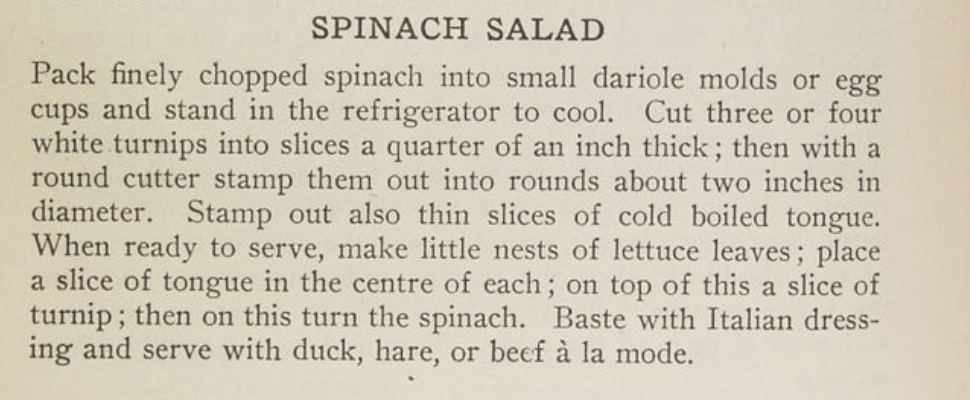

Domestic scientists, like Lilian Tingle, wanted to transform American cooking by rationalizing and intellectualizing middle class kitchens. Domestic scientists obsessed over ‘dainty,’ ‘clean’ foods. During this period people strongly associated salads with delicate femininity. Even housewives who employed a cook would often prepare salads themselves. But salads were messy, so many salad recipes went to great lengths to transform the salad into a dainty, uniform dish.2Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century. North Point Press, 1986. Sometimes that meant individually arranging every lettuce leaf, or drowning everything in white sauce. Gelatin offered a means of containment.

A Brief History of Gelatin:

Before the 19th century, making gelatin was similar to making stock. It required 8+ hours of boiling a pot full of hooves and hides3Kristin Holt (blog), April 7, 2021, http://www.kristinholt.com/archives/24150.. Anyone could make and eat gelatinized dishes, after all, gelatin is made from scraps. But for elites, chefs perfected gelatin to create elaborate free-standing molded centerpieces. Starting in the early 1500s, increasingly elaborate gelatinized desserts were status symbols in England, and later the U.S. In the 1840s, industrialization brought store-bought gelatin sheets (of varying reliability), and then powdered gelatin.4Peter Brears, Jellies & Their Moulds (Prospect Books, 2010) Instead of homemade calves-foot jelly, powdered gelatin became the norm, as companies marketed it to consumers as an early industrialized food product. In the early 20th century, many recipe writers and domestic scientists adopted gelatin and it became a common ingredient in desserts and salads.5McNamee, A., and A. Service. “Jell-O Page.” A. Service, January 2022. http://alliaservice.com/my-projects/jello/.

Making the Aspic

This week I made a tomato aspic, or jellied tomato salad, as requested by Mrs. R.E.C. in 1925. Tingle gave Mrs. R.E.C. upwards of six recipes for both tomato jellies and fruit salads, and a lot of general advice. The aspic was by far the simplest recipe I’ve made so far. The only ingredients were: tomato puree, beef broth, chili sauce, salt, paprika with chopped celery and grated cheese to garnish. The results were quite unpleasant.

I set some of the tomato aspic in a pan to cut into cubes, as Tingle suggested, and the rest in a silicone ice cube tray, in a vain attempt to make cute gelatin flowers. However unmolding proved more difficult than I’d anticipated. The gelatin didn’t pop easily out of the molds, and instead I created a massacre of tomato and celery that looked hauntingly like raw meat.

The aspic set in the pan released much more easily. Tingle’s suggested presentation was serving the ‘salad’ on a bed of lettuce, cut into cubes, sprinkled with chopped celery and grated cheese. Once cubed, the aspic looked a lot like raw sushi fish, and the overall presentation, while not the most appetizing, was very striking. Unfortunately, there was nothing left to do but try the aspic. For our first bites we each took a cube of aspic without the garnish. The taste was overwhelming, intensely tomatoey and strangely spicy (because of the chili sauce e.g. sriracha). The beef broth left a distinctly meaty aftertaste. I wasn’t expecting to love it, but it really was worse than I could have imagined. The flavor was so strong, combined with the cold, slimy texture of the gelatin. After our first bites, we tried the aspic again, this time with the celery and cheese. Against all expectations, it was much better with the garnish. The cheese cut the flavor somewhat, the celery gave it texture, and in the end it tasted sort of like a bad cold chili, not entirely unpleasant. Out of the four of us who tried it, no one liked it at all. Even with the garnish it was only barely tolerable.

So what does this say about Americans’ taste in the early 20th Century? Well, savory gelatin salads were certainly more widely eaten, and it would be naive to think that no one genuinely enjoyed them. Of course we don’t know if people enjoyed this salad. It could have been a recipe that few people made or enjoyed. We also weren’t eating it in the larger context of a meal. Tingle says that tomato jellies are a good accompaniment to other foods, especially leftover meats. Putting meat in the jelly might stretch leftovers to another meal while still preserving the family’s expectation of a fresh home-cooked dinner prepared every night. Eating the salad more like a relish or a garnish might significantly improve it, and eating it during a time when savory gelatin was all the rage would also help. While I think of the group of friends who tried the aspic as adventurous eaters, none of us have the same cultural contexts as Tingle’s correspondents. But I don’t want to overstate the case. There were probably a lot of Oregonians in 1925 who would have hated the tomato aspic. Just because a recipe was in the paper doesn’t mean everyone likes it.

Notes

If you’d like to learn more about the fascinating history of gelatin and Jell-O check out this zine I co-wrote with A. McNamee!

Thanks to Audra, Haley, Kira, and Max for their photos and willingness to try tomato aspic.

For references, click on in-text footnotes or visit this page for a full bibliography.